The venture capital pipeline that flowed through Silicon Valley Bank to fuel the growth of young companies was under stress from inflation and rising interest rates before the lender failed. While downstream impacts on funding and innovation aren’t yet clear, the potential implications are serious enough for companies to re-examine vendor portfolios.

Short-term disruption introduced wariness into the tech startup ecosphere that will last until there is more confidence in cash flows, Brad Haller, senior partner in the mergers and acquisitions practice at technology consulting firm West Monroe, said in an email.

“That delays innovation in the tech economy overall,” Haller said.

Tech leaders with suppliers who banked with SVB could set aside immediate concerns about the viability of those vendors when federal authorities stepped in to shore up existing deposits shortly after a run forced the bank’s seizure. But uncertainty about the stability of tech startups, which are volatile by nature, persists.

SVB’s support role went beyond banking, according to Ronak Doshi, technology practice partner at IT consulting and research firm Everest Group. It extended to “networking events and summits and to product, risk and financial advisors,” he said.

The institution also added to the pool of available capital. Venture debt, a special type of loan designed for early-stage, high-growth startups that have funding but lack positive cash flow, was central to SVB’s business.

“They were a key venture debt funder,” said Scott Bickley, practice lead and principal research director focused on vendor management and contract review at Info-Tech Research Group. “It provided tech startups with loans based on the size of their VC funding, which gave them access to funding above and beyond their core equity.”

SVB’s failure also interrupted lines of credit vital to business operations. This may create short-term problems for some startups, Thomas Phelps, CIO and senior vice president of corporate strategy at Long Beach, California-based enterprise software company Laserfiche, said in an interview with CIO Dive.

Laserfiche contracts with over 100 vendors for software and IT services, although only about a dozen banked with SVB, according to Phelps.

While those vendors remain secure, there’s still some risk in the larger ecosphere, Phelps said.

“IT leaders should be aware that they’ve got some runway now,” said Phelps. “But what’s going to happen to these tech startups if they lose access to those credit lines down the road?”

Long-term concern

Disruption in Silicon Valley could reach into the middle of enterprise IT portfolios via third-party providers dependent on the supply chain, Wendy Pfeiffer, CIO at San Jose-based cloud software company Nutanix, said during a Wall Street Journal CIO Network panel in March.

“I’m worried about three months from now as some of their key components are potentially compromised,” Pfeiffer said.

Startups that weathered the initial crisis may have additional exposure as the cost of capital rises and lenders exercise caution.

“Higher quality companies will come through this, but a lot of innovation could be impacted,” Vineet Jain, CEO and co-founder of Silicon Valley software company Egnyte, told the panel.

Vendor exposure is always a concern for the enterprise, but third-party risk should now be a more salient issue, according to Forrester. While onboarding innovations from startups will continue, a rigorous vetting process should be the norm, the analyst firm said in a recent blog post.

IT leaders should continue to test promising products with an eye toward mitigating risk by scrutinizing vendor financials and identifying backup suppliers with comparable offerings, Forrester said.

“Supply chains and hidden dependencies are something I’m always paying attention to,” Jason Conyard, CIO and SVP at Palo Alto, California-based cloud computing company VMware, told CIO Dive. “Business continuity planning isn’t just about earthquakes and hurricanes. It includes supply chain challenges, geopolitical situations and economic uncertainty.”

Better vetting

Vendor vetting is integral to building stability, resilience and security into enterprise IT.

“When you bring new vendors into your technology ecosystem, you have to assess the security data privacy implications, as well as the risk of third-party vendors providing services and technologies,” Laserfiche’s Phelps said.

If a vendor is a public company, Phelps reviews earnings reports. For those that are privately owned, the process is more complex.

“I want to know how long they've been in business, who their founders are, what funding series they are in and how much cash they have,” Phelps said.

It’s also important to know who your vendors do business with, not just for banking but for technology and services that can disrupt the supply chain.

“A lot of vendors, even tech startups, rely on the services of other companies to provide services to you, so it can get very hairy very quickly,” Phelps said.

As the dust settles on SVB, M&A activity may pick up in Silicon Valley, as companies prepare for opportunistic buyouts of ailing startups, according to Forrester. This too can pose a risk, changing the relationship between a vendor and its clients.

“Vendors can close up shop very quickly,” Phelps said. “As part of our process, we look at the terms of our contracts with these vendors, what happens if the vendor is acquired by a competitor and how we get access to our data upon exiting that agreement.”

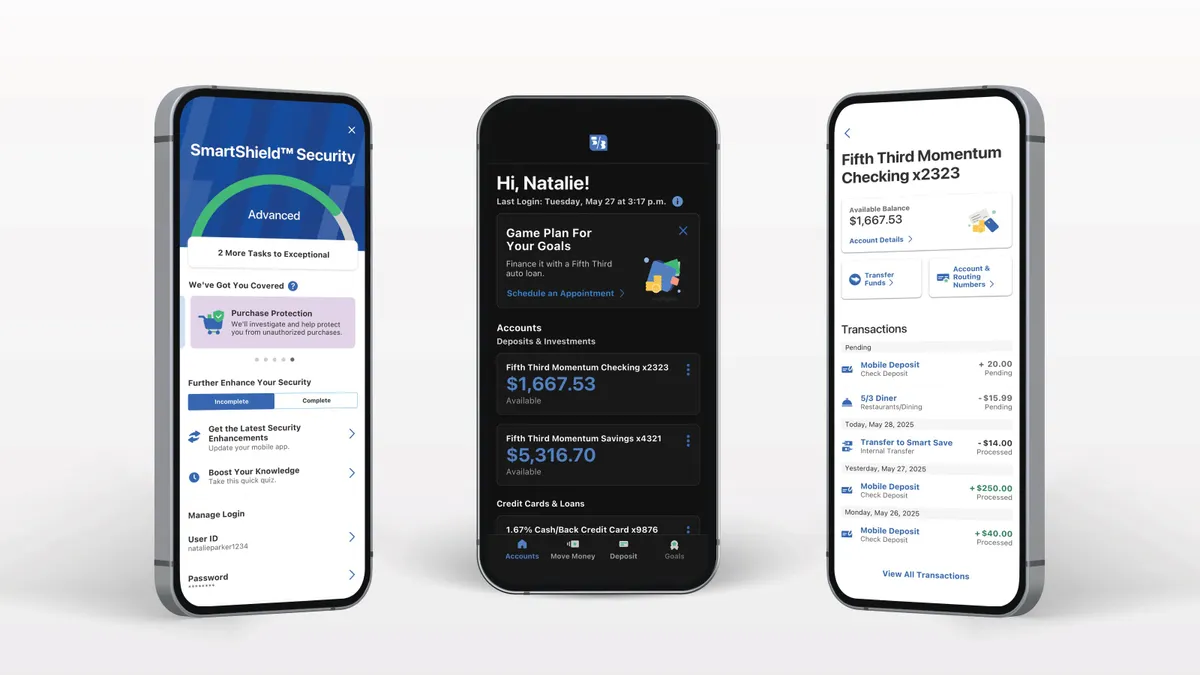

For the startups, self-vetting may be in order, particularly on the banking side.

“The big thing on everyone’s mind is treasury and diversification,” AJ Bruno, co-founder and CEO of software startup QuotaPath and a former SVB client, told CIO Dive. “Now it's our fiduciary responsibility to ensure that we have a multithreaded approach, which was never really the case in the past.”

Asking where a startup banks and whether M&A or IPO activity is on the horizon is now a priority.

“We’ve always asked similar questions, but now we’re asking more of those questions and going more in depth,” said Phelps. “And it's coming up in the first part of our conversation rather than at the tail end.”