Banks and fintechs have been partnering for years, a symbiotic relationship that has allowed fintechs to scale and traditional financial institutions to expand the suite of products they offer to consumers.

But a growing debate over how consumer financial data should be shared has pitted industry incumbents against fintechs in recent months.

Screen scraping and Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) were among the topics discussed at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s (CFPB) symposium on Consumer Access to Financial Records on Wednesday, and several panels highlighted the opposing views of banks and fintechs when it comes to collecting consumer data.

"Screen scraping has reached its current peak of benefit," said Natalie Talpas, senior vice president and digital product management group manager at PNC Bank, referring to the method of data collection where a third-party requests credentials from a customer’s account in order to “scrape” information that is then provided to a fintech.

"At PNC, we think data security is fundamental in these agreements. When you have entities that have access and are storing the same type of information that we as financial institutions store — and that our customers trust us with to keep secure — when you have this type of data outside of our walls, we think it's very important that those entities are subject to the same type of federal supervision or cyber security standards that banks are," she said.

"We're in the trust business. If we don't get that part right, we will lose everything about our banking business."

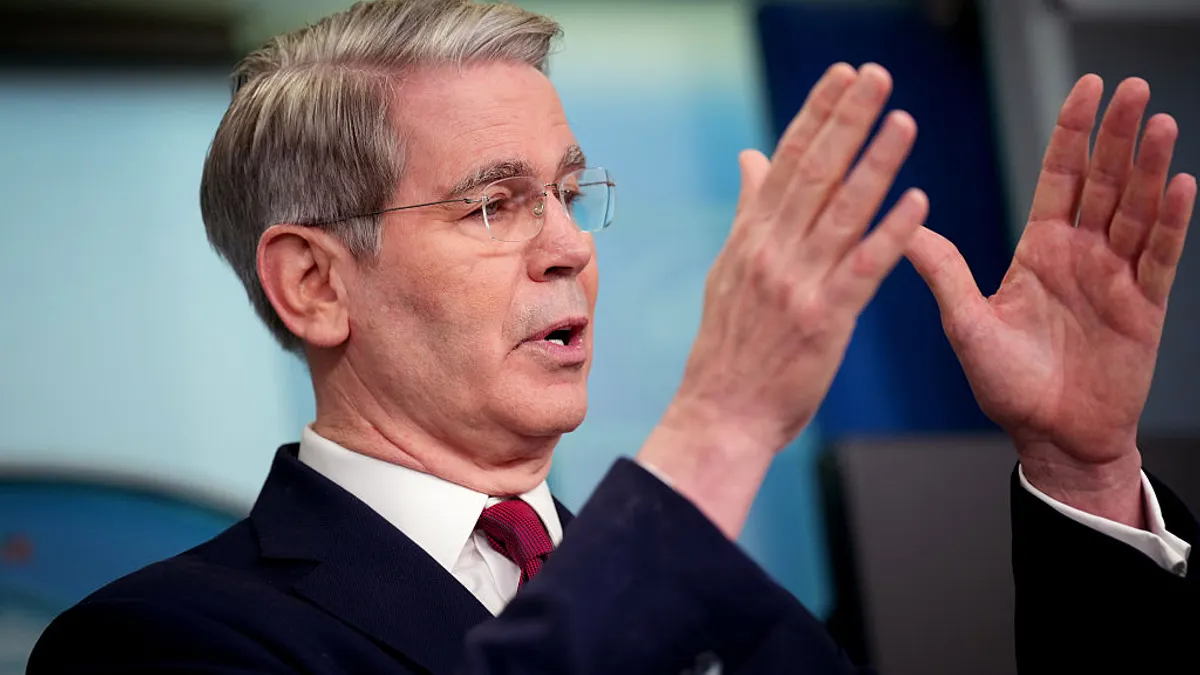

James Reuter

CEO, President of FirstBank

Using account log-in credentials provided by the customer, data aggregators such as Plaid and Yodlee have used screen scraping to collect information from users’ bank accounts for years.

The practice enables Plaid to connect accounts to fintechs such as peer-to-peer (P2P) payment platform Venmo and robo adviser Betterment. But recent security and policy changes at several large banks have blocked some aggregators from accessing passwords.

PNC started blocking aggregators from gaining access to customers' account numbers and routing numbers last fall after it said it identified "multiple different aggregators" attempting to circumvent the bank's security protocol.

The security upgrade prevented Plaid from accessing information it uses to facilitate transactions between bank accounts and Venmo.

JPMorgan Chase announced it will also ban third-party apps from accessing customer passwords and instead issue tokens for access to its own API-based dashboard. The bank said fintechs have until July 30 to sign new data access agreements and agree to a plan to stop using customer passwords to gather data.

As financial institutions like JPMorgan Chase and PNC aim to boost security through the implementation of their own APIs, experts told Banking Dive they expect more will follow.

But some fintechs say the migration toward APIs could come at a cost to consumer choice.

"The concern I have is, as you transition from the screen scraping environment to the API environment, how do you make sure that consumers don't have their choices restricted from what they are currently?" John Pitts, policy lead at Plaid, said. "And if every player is independently deciding which app is okay for their customers to use, they may override the decision the consumer has already made."

As more banks adopt APIs, Pitts said one of the biggest challenges for fintechs is negotiating agreements with the thousands of financial institutions that exist in the U.S.

"As you transition from the screen scraping environment to the API environment, how do you make sure that consumers don't have their choices restricted from what they are currently?"

John Pitts

Policy Lead, Plaid

"It's very hard to scale," he said.

Jason Gross, co-founder and CEO of fintech startup Petal, said his company experiences daily interruptions of its business due to an inability to access consumer data.

"It threatens the viability of us and others that would use this technology to expand access and lower costs for consumers," he said.

The fintech startup uses bank account transaction information in its underwriting process to facilitate the issuance of consumer credit card products.

"When we look at the data, we see between 40 and 60% of attempts to link a bank account that failed on our system." Without the ability to view a "full financial picture," Gross said those customers can be denied approval or charged a higher annual percentage rate.

"Whenever you give an individual FI the ability to say, we don't want to approve of this use case … I think you end up in a situation where the consumer’s choices could potentially be vetoed," Pitts said.

The long tail

Nick Thomas, co-founder and chief technology officer of real-time financial data access provider Finicity, said that while credentialed access to financial data is not the best approach, "It has served us really well for 20 years."

"We need to make sure that we, as an industry and as regulators and lawmakers, understand that screen scraping is not evil," he said. "The use of credentials is something that we really want to get away from. We want to move to tokenization access. But there is a long tail of financial institutions. And it's going to take time for these API standards to proliferate … Generally speaking, consumers have spoken. They want access to their data. And screen scraping has been the only way that that data has been made available."

James Reuter, CEO and president of FirstBank, agreed that there is a "long tail" of banks that will take some time to develop their own APIs.

"It's going to take us a while to get there, but screen scraping is not the way we want to do business," he said.

Becky Heironimus, managing vice president of customer platforms, data ethics and privacy at Capital One, said that while screen scraping might not be "evil," it can be dangerous when mistakes are made.

"We've seen instances where screen scraping has caused changes to accounts and mistakes to happen because there are not a lot of controls over it," she added.

Giving consent

Pitts said the growing demand for financial services products shows that consumers have decided they want to share their data with third-parties. Talpas disagreed.

"I think the fact of the matter is that they're not able to decide because the consents are not consistent or not transparent, and they're not clear," she said. "Our consumers, unfortunately, don't understand what they're agreeing to. They don't know that there might be an intermediary or a data aggregator that's also collecting the information."

Christina Tetreault, senior policy counsel for Consumer Reports, said privacy policies across most industries are generally broad and sweeping, with terms such as, "We collect your information for analytics," and "We share with trusted partners."

"That type of information is not helpful," she said, adding that most consumers don’t even read the privacy policies they agree to.

Reuter said banks want to allow their customers access to fintech products, but they want it to be transparent, where the customer has complete control.

"We're in the trust business. If we don't get that part right, we will lose everything about our banking business," he said. "And that's not something we take lightly."