A growing number of banks with older management teams and small private fintechs are coming to market each day, but merger and acquisition activity is likely to remain quiet until the Federal Reserve begins rate cuts, one bank CEO predicted.

That includes banks with “an older team that’s been fighting the war for 20 years, looking for an exit and a way to move onto retirement,” or “younger companies that understand they need critical mass to really succeed,” said First Internet Bank CEO David Becker in an interview this week.

M&A activity has started to surface, Becker said, pointing to Wintrust’s $510 million acquisition of Michigan’s Macatawa Bank, announced this month. But valuation of assets remains an issue.

“The mark that a lot of institutions would take on their assets would make it a pretty tough pill to swallow on the purchase price,” Becker said. Some companies will be forced to find a buyer if they’ve reached the end of their runway, “but the real activity will come later as rates hopefully start to drop a little bit.”

When it comes to making acquisitions or being acquired, First Internet Bank engages in those conversations, but “the pricing and components today just don’t really make sense,” said Becker, who founded the bank in 1999.

The $5.2 billion-asset bank, based in Fishers, Indiana, looks at both banks and fintechs in assessing acquisition targets. Because First Internet Bank — the first Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.-insured digital-only institution — doesn’t have any branches, the bank isn’t interested in scooping up a community bank with a network of branches, Becker noted.

It’s more likely to pursue a fintech or smaller bank that brings First Internet a fee generator or low-cost deposits, a foot in the door of a new vertical, or presents an opportunity the lender can roll out nationally, he said.

Smaller bank M&A, in particular, is needed, as it’s become more challenging for smaller institutions to remain viable long-term, said Brian Graham, partner at advisory firm Klaros Group.

“It’s expensive to be in the business of banking,” Graham said.

Banks face fixed costs related to technology and regulation, and those have risen, he noted.

“The natural economic response is to be bigger, to spread those fixed costs over a larger base,” Graham said. “And that’s very true for banking.”

The cost of competing is also putting pressure on smaller banks, many of which realized during the COVID-19 pandemic the importance of adeptly serving clients online, or risk losing them, Becker said. Many of those lenders also don’t have the wherewithal to compete with bigger banks on deposit or CD pricing, he added.

Building a BaaS team

In 2022, after the parent company of First Century Bank scrapped First Internet’s planned $80 million acquisition of the Roswell, Georgia-based bank, First Internet pivoted.

First Century, with an established payments business and strong compliance team, would have given First Internet a head start, “no question,” in expanding into banking-as-a-service, Becker said. As the deal dissolved, First Internet opted to build its own BaaS infrastructure internally so it could serve fintechs, Becker said. Although that endeavor took the lender more time, he estimates it might have been just as involved as merging with First Century.

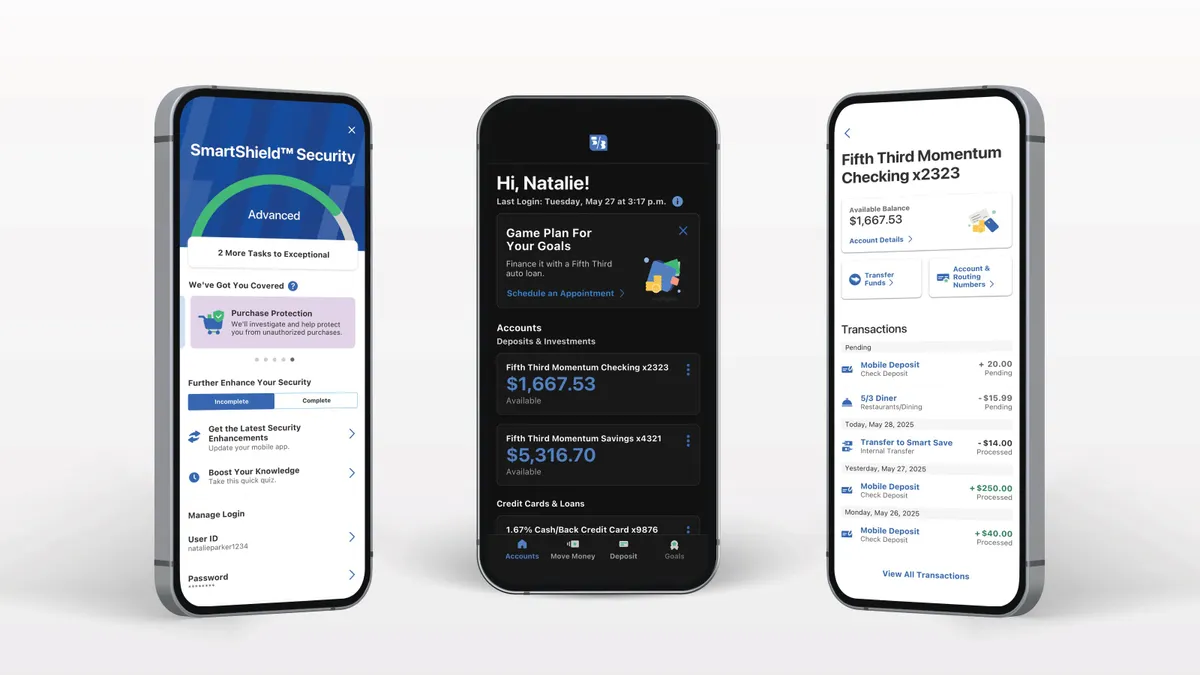

First Internet now has about a dozen dedicated BaaS employees handling compliance, operations and onboarding, and continues to add employees in that division, Becker said. The bank counted 290 employees as of the end of last year, according to its most recent annual filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Expense management fintech Ramp is First Internet’s largest BaaS client: The bank processes $1 billion in payments each month for Ramp’s card services, Becker said; the bank began working with that fintech in late 2022. First Internet also counts small-business lending fintech Jaris as a client.

The bank’s BaaS-brokered deposits more than quintupled from 2022 to 2023, amounting to $74.4 million at the end of last year, according to the bank’s annual filing. First Internet had $4.1 billion in deposits in total at the end of last year.

In recent months, banks offering banking-as-a-service to fintechs have faced more regulatory scrutiny, which has led some banks to leave the space.

“A lot of the community banks that jumped in, they didn’t understand all the compliance issues related to it,” Becker said.

Some smaller banks that got into BaaS, looking for cheap deposits and fee revenue, opened more accounts on a monthly basis than they had in two years, and soon realized they were facing a new level of scrutiny, Becker said.

Regulators “can’t really control or examine or work with a fintech company, so they’re looking for the bank to kind of be an extension of the regulatory side,” he said. “And a lot of institutions don’t have the capacity and the skill-set to do that.”

There are digital tools to manage that, but those can be costly, while doing things the “old fashioned way” becomes a challenge for banks that fear tripping up on the compliance side, Becker added.