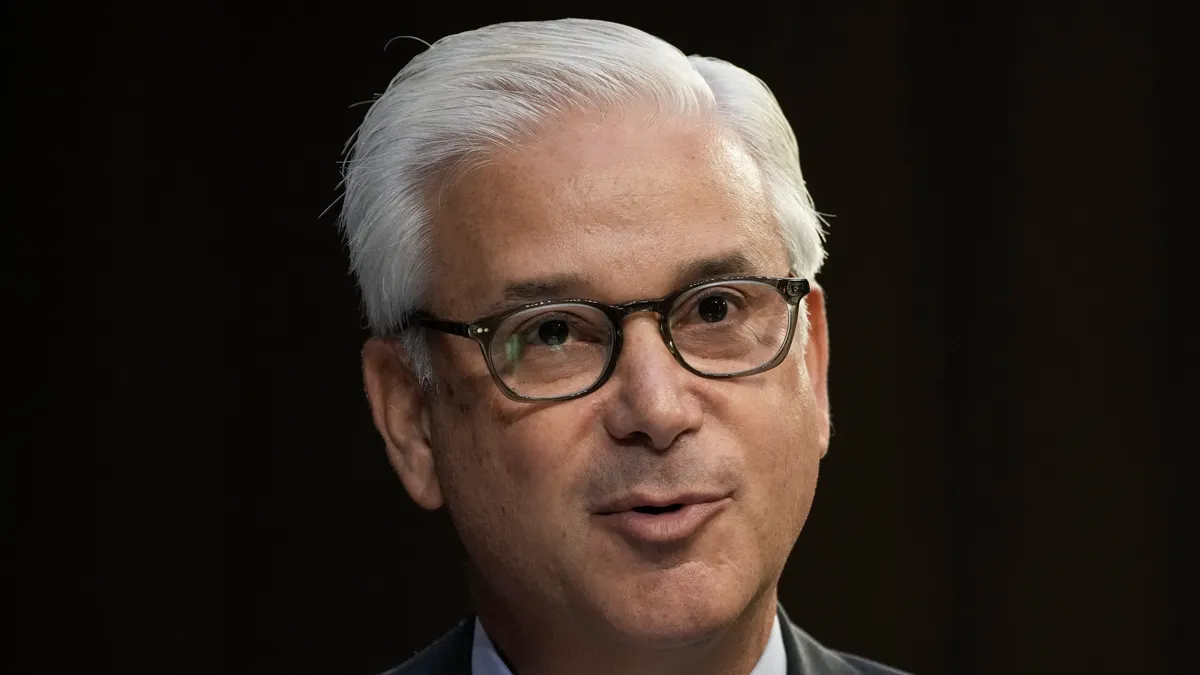

Wells Fargo CEO Charlie Scharf expects the bank to be more aggressive in going after deposits and lending once the asset cap it’s under has been lifted, as the lender has had to carefully manage its activities due to that regulatory action.

The most important aspect of the lifting of the $1.95 trillion asset cap isn’t “the pure economics,” Scharf said during Friday’s first-quarter earnings call. “It is still a reputational overhang for us.” The cap, imposed on the bank by the Federal Reserve in 2018, is tied to its 2016 fake-accounts scandal. Wells currently has about $1.7 trillion in assets.

The related consent order being lifted in February “was extremely important” in terms of public perception, Scharf said Friday. The Office of the Comptroller of the Currency said the San Francisco-based bank’s “safety and soundness” and its compliance with regulations prompted the agency to terminate the consent order.

The removal of the asset cap is “an important factor in terms of how we’ll be viewed, as opposed to what we’ll actually do,” Scharf said.

But the asset cap has also presented an opportunity cost, as it has limited Wells in some areas, Scharf noted. Since he took the helm of the bank in 2019, six consent orders have been resolved, as Wells has sought to move past the scandal.

Bank executives have said they envision that cap remaining in place into 2025, Bloomberg has reported. Scharf did not comment Friday on when the asset cap may be lifted.

“Across all of our businesses, we’ve been very, very conservative in what we have asked people to do, because we don’t want to have an asset cap issue,” Scharf said.

Proactive management by the company to keep Wells below the asset cap has included identifying “places where we have gone and said, ‘Please make your business smaller,’” as normal deposit flows and consumer businesses present some asset pressure “and we need to offset that someplace,” Scharf said.

Particularly within its trading businesses, the lender has limited its ability to handle some low-risk activities, such as financing customers. That’s meant Wells hasn’t captured as much trading flow as it might have otherwise, Scharf said.

In the bank’s corporate businesses, executives have been careful “to encourage our bankers to bring in sizable corporate deposits that weren’t clearly operational deposits,” Scharf said.

In some cases, Wells has been “a little bit more aggressive about asking them actually not to have it here, because we wanted to make room for other things that we thought were really important strategically,” he said. Those include “not being closed for business on the consumer side, which those folks would not understand is hopefully just something that’s temporary,” Scharf added.

When the bank is no longer constrained by the cap, Scharf envisions opportunities for Wells to further invest in its consumer or wealth businesses, to build out its product offerings and to be more aggressive in terms of lending and deposits.

It’s “the ability to grow in the things that we’re confident at, that we do well, that we have – in some ways consciously, and in some ways unconsciously – restrained the company from doing,” Scharf said. “You’ve seen others that don’t have those constraints, but have the quality franchise as well, and see how they’ve benefited not just versus us, but versus the broader banking set,” he added, about big bank peers.

Goldman Sachs analyst Richard Ramsden said once the cap is lifted, he expects “to see more rapid growth in deposits, securities, the trading business, and parts of the lending business."